Naval History Magazine

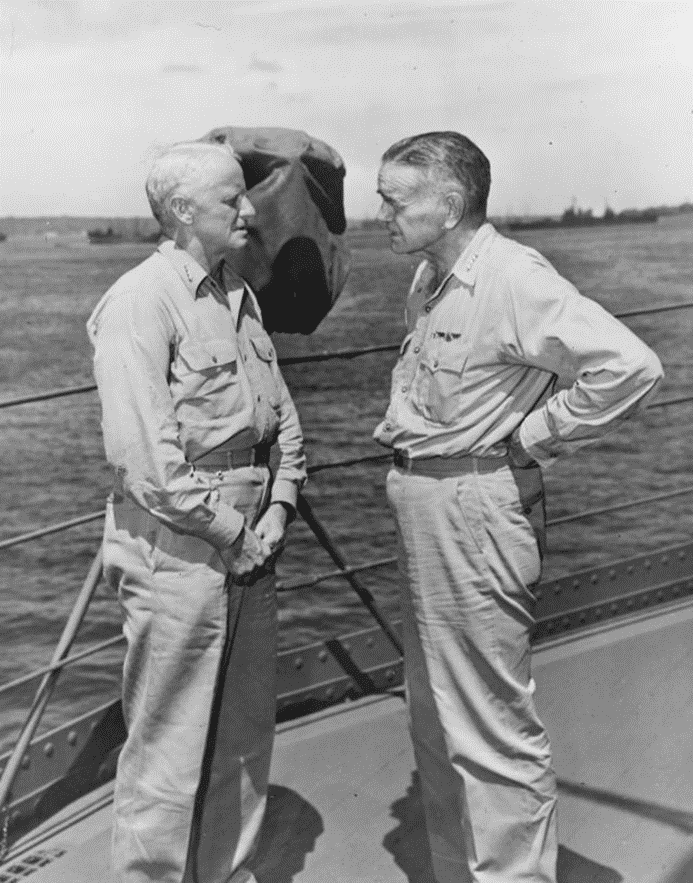

Admiral William Halsey confers with Major General Alexander A.

Vandegrift, USMC, at South Pacific Force headquarters, Noumea, New Caledonia,

in January 1943.

(U.S. NAVAL INSTITUTE PHOTO ARCHIVE)

Under the Radar:

Admiral Halsey at the End of World War II (Part II)

Would the surrender hold?

By Rolland Kidder

October 2022

Naval History Magazine

ARTICLE

Two days later, on 21 August, MacArthur acknowledged his

official approval of the initial landings proposed by Halsey, and sent to

Halsey the following order:

In

view of the fact that HAYAMA, ZUSHI, and KAMAKURA have been selected as

headquarters area of the Supreme Allied Commander and advice given by Japanese

emissaries that the initial landings would be in restricted areas, it is

considered advisable to put into effect the general provision of your Plan 2,

with not to exceed what is normally considered to be a regimental combat team.

. . . Landing force as limited above is acceptable. Brigadier General Clement

[Marines] will report by radio upon my assumption of command. . . . His force

will land in the vicinity of YOKOSUKA and occupy the general areas:

URAGA-KUBIRI-FUMAKOSHI [FUNAKOSHI]-YOKOSUKA,++ all inclusive. . . . Airfield for

11th Airborne and H Hour will designated by SCAP. . . . The emissaries were

directed to have the area evacuated of Japanese troops but we must be alert to

guard against surprise.2

Halsey moved quickly upon receiving those orders from

MacArthur. Eighteen hours later, William F. Halsey, Commander 3rd Fleet,

announced that he had complied with MacArthur’s directive:

“Japan

has surrendered. . . . Army Forces have seized ATSUGI airfield and CINCAFPAC

[MacArthur] Advance Headquarters are established there. CTF 31 Forces hold

YOKOSUKA NAVAL BASE and airfields and 3rd Fleet forces are disposed in the

TOKYO BAY-SAGAMI WAN AREA. 3rd Fleet Air is patrolling HONSHU and the TOKYO BAY

AREA. KANOYA airfield KYUSCHU is held by our occupation forces . . .” 3

The rest of Halsey’s message outlined how the timing of

additional landings would occur and directed the fleet to assist 8th Army and

other forces in establishing the occupation. Substantial detail is given for

the activities of COM3RDPHIB (Commander 3rd Amphibious Force, Vice Admiral T.S.

Wilkinson.) But the message is unequivocal—on 22 August 1945 (Japan time,)

“Bull” Halsey had men ashore at Atsugi and Yokosuka in Honshu and at Kanoya on

Kyushu Island.

In another message from Halsey (3rd Fleet) to Eichelberger

(8th Army) late on 21 August, Halsey added more detail, writing that that he

“will execute my plan 2 including occupation of forts vicinity FUTTSU SAKE

which I will arrange to have vacated when I am met by emissary off OSHIMA.”4 This

communication was not date-specific as to the FUTTU SAKE operation, but it

likely happened on or about 22 August when the other initial landings occurred.

On 28 August, Halsey’s fleet finally would link up with a Japanese destroyer to

escort the major ships of the 3rd Fleet, which would participate in the Tokyo

Bay surrender ceremony. Since FUTTU SAKE is a promontory flanking the eastern

entrance to Tokyo Bay, it would make sense to have it secured.

Though not specifically stated, it is reasonable to assume

from these messages that one purpose in deploying these initial landing parties

was to test the validity and seriousness of the Japanese surrender. Would the

surrender hold? It was known that there were elements, especially in the

Japanese Army, that were opposed to the surrender. Would Japanese soldiers,

sailors, and airmen obey their Emperor and lay down their arms? Fortunately,

for those Americans who were in these relatively small initial landing forces,

they did.

Halsey followed up his general Op-Order on 22 August with

his “Air Plan, Annex D my Op-plan 11–45.” The last paragraph could have

relevance to what was being done by one Ensign F. Haydn Williams. It reads:

“Para. 3. Garrison. (A) MAG 31, (B) NATS landplane unit. 1. garrison squadrons

and ground echelons will be assigned appropriate tasks when installed.”5 This

paragraph seems almost purposely vague, though it also seems likely that these

units had been deployed that day with the initial landing force at Atsugi. Williams

was a part of the Navy support effort to establish a Naval Air Transport System

(NATS) base in Japan. This unit eventually would be sent to the Kisarazu

airfield on the east side of Tokyo Bay to establish the NATS service base for

the Tokyo Bay area.

In the “Nimitz Only” section of messages, one dated 21

August makes specific reference to a “Naval aviation member advance party.” It

was sent directly from KINCAID (7th Fleet) to NIMITZ in Guam and seems to be a

“back-channel” communication advising CINCPAC of developments with this early

advance party going into Japan:

Captain

Carroll B. Jones, Naval aviation member advance party to TOKYO was informed by

GHQ [MacArthur headquarters] today that he would not be allowed to inspect and

obtain 1st hand information on airfield and facilities YOKOSUKA. Party will be

kept together vicinity ATSUGI to prevent possible incident. All available

information field and facilities YOKOSUKA is to be supplied to advance party by

Japanese.6

Either the naval aviation “advance party” was in Atsugi or

about to go there, but MacArthur did not want them at Yokosuka. It would seem

likely that this “naval aviation advance unit” is the outfit to which Ensign

Williams was assigned.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and Admiral William Halsey confer

on board USS Curtiss (AV-4) at Button Naval Base, Espiritu

Santo, New Hebrides, 20 January 1943.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

It appears that on the same day (Japan time) that Nimitz

sent this message, General MacArthur made a move to establish a naval air

station that could accommodate large planes like the R5D: “The

Reconnaissance Troop of the 11th Airborne Division made a subsidiary airlift

operation on 1 September, flying from Atsugi to Kisarazu Airfield. This

airfield was occupied without incident.”8 According to F. Haydn Williams’ conversations with me,

he was on this airlift operation that opened Kisarazu. He said that everyone

riding in the planes involved was a bit scared. They had no idea whether they

would meet friend of foe when they arrived at the Kisarazu Airfield. As it

worked out, there was no problem, and the field was occupied without

opposition.

It is also interesting to note that in all the U.S. naval

air attacks on Japan in July–August 1945 cited in the Gray Book,

there is no mention of Kisarazu. Could it have been on a no-hit target list? It

is cited by MacArthur in Reports as being the airport from

which the Japanese emissaries left for Manila on 19 August.9 Perhaps

the Kisarazu airfield had been spared destruction because a decision had been

made to leave at least one airport in the Tokyo Bay region untouched so that

air traffic to and from the country was still possible at war’s end. Whatever

the reason, on the east side of Tokyo Bay, Admiral Nimitz and the Navy now had

an airfield of their own that could handle large land-based aircraft..

One is reminded of the adage that “all politics is local,”

meaning, in this instance, that people tend to rely on people they already know

and trust. MacArthur had gained the confidence of Navy men like Admiral

Sherman, and men like Kincaid (7th Fleet,) Wilkinson (3rd Amphibious Force),

and Brigadier General William Clement, who had been with him during the

campaigns in the Southwest Pacific, New Guinea, and the Philippines. But the

key to pulling the Navy assets together during the two weeks leading up to the

2 September surrender signing in Tokyo Bay had been another Navy friend, one

William F. “Bull” Halsey.

Halsey and MacArthur

MacArthur and Halsey were close. On a least three occasions

during fighting in the South Pacific, Halsey had met with General MacArthur at

his headquarters in Brisbane, Australia. The occasions cited here are all taken

from Halsey’s autobiography, Admiral Halsey’s Story. In this book,

Halsey portrayed himself as a rather “down-to-earth” folksy guy who did not put

on a lot of “airs” or always needed to be catered to—juxtaposed with

MacArthur’s reputation of being quite aloof and overbearing. Yet those

differences did not disrupt their first or any subsequent meetings.

In early April 1943, after the battle for Guadalcanal had

ended, Halsey went to Brisbane to discuss with MacArthur follow-up operations

in the Solomon Islands and the Southwest Pacific area. According to Halsey’s

account, recognition of a common interest broke the ice at the first meeting

—Halsey’s and MacArthur’s fathers had been friends 40 years earlier in the

Philippines. “Five minutes after I reported, I felt as if we were lifelong

friends,” Halsey wrote. By the end of the meeting, “[MacArthur] accepted my

plan for the New Georgia operation.”10 It was obvious that MacArthur liked Halsey’s fighting

spirit, and they generally agreed on joint Navy/Army strategies as they related

to fighting the Japanese in that part of the world.

There was also another, more visceral connection: their

backgrounds in the military. As Thomas Hughes noted in his book Admiral

Bill Halsey: A Naval Life, “Halsey never spent a day outside the cocoon of

the American military, a trait he shared with only General MacArthur out of all

officers in the nation’s history.”11 The lives of both men had been carved by being the

sons of men who spent their entire lives within the confines of the Army or

Navy.

The chemistry between MacArthur and Halsey was also

complemented by familiarity between their staffs. As Halsey observed, “There

was an unusual bond between our staffs: My Chief of Staff’s son, Captain Robert

B. Carney, Jr., had married MacArthur’s Chief of Staff’s daughter, Miss Natalie

Sutherland.”12 There is nothing better for command relationships in

the military than when competing staffs can get along.

Later, in December 1943, prior to going to Pearl Harbor to

see Admiral Nimitz and then on to Washington to meet with Admiral King, Halsey

would go back to Brisbane to, as he wrote, “Take leave of General MacArthur.”13 This is

Navy language used in describing when one is parting from the command of a

superior officer. Halsey knew who was “the boss” in this relationship.

Reflecting the camaraderie of the meeting, MacArthur made a pitch to Halsey for

him to become the Navy commander in the Southwest Pacific area: “Bill, if you

come with me, I’ll make you a greater man than Nelson ever dreamed of being.”

Halsey retorted: “I said that I was flattered, but in no position to commit myself;

however, I’d certainly tell King and Nimitz about his offer. I did and that’s

the last I heard of it.”14 At the same meeting, Halsey and MacArthur both talked

about the idea of “island hopping” and leaving Japanese fortress islands like

Rabaul to “wither on the vine,” a concept that met with growing support both in

the Pacific theater of the war and in Washington.

February 1944

Halsey then described a third meeting with MacArthur, which

took place in February 1944. It was after an island called Manus had been taken

and a dispute developed about who would control it—Army or Navy. Nimitz had

sent a dispatch to Admiral King in Washington and copied MacArthur on it

recommending that Halsey’s area of operations be extended to include Manus.

When he got to the meeting, Halsey described MacArthur as

“fighting to keep his temper” and that MacArthur “went on for a quarter of an

hour” about it and suggested that only the 7th Fleet and British units be

allowed in the port until “the jurisdiction of Manus” was decided. When given

the chance, Halsey responded that in his view such an action “would hamper the

war effort” and that MacArthur should not consider it:

His

staff gasped. I imagine they never expected anyone would address him in those

terms this side of the Judgment Throne. I told him that command of Manus didn’t

matter a whit to me. What did matter was the quick construction of the base.

Kenney, or an Australian or an enlisted cavalryman could boss it for all I

cared, as long as it was ready to handle the Fleet when we moved up New Guinea

and on toward the Philippines.” The next day, MacArthur said: “You win, Bill!”

Then he turned to Sutherland and said: “Dick, go ahead with

the job.”15 Before leaving the South Pacific for the last time, Halsey

would be granted the Army’s Distinguished Service Medal at a ceremony in

Noumea, New Caledonia, in June 1944.16 He was now a recognized MacArthur man.

August to September 1944

When Halsey returned to the Pacific after a break, he would

meet again on MacArthur’s turf at Hollandia, New Guinea, in September 1944.

Though Halsey describes it as a meeting with “MacArthur’s staff,” it is hard to

believe that General MacArthur would have missed the meeting.17 Halsey

and MacArthur were planning one more campaign together before they would join

hands in Japan at the end of the war—Halsey’s fleet would be supporting the

Army landings at Leyte in the Philippines and would be attacking Japanese

targets throughout the Philippine archipelago.

Halsey would again return to the United States in the winter

and spring of 1945. By the time he returned to the Pacific, MacArthur had

finished the Philippine operation and was living and headquartered in Manila.

Halsey and MacArthur had lunch together there on 14 June 1945.18 Undoubtedly,

much was discussed—including the pending end of the war. Halsey had met with

President Roosevelt for an hour discussing “subjects so secret that I would

have preferred not to know them” while he had been in Washington.19 One

must assume that MacArthur’s role and the need for the Army and Navy to work

toward a common end in finishing the war also must have been a part of that

conversation.

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur signs the Instrument

of Surrender, as Supreme Allied Commander, on board the USS Missouri (BB-63),

2 September 1945. (Naval History and

Heritage Command)

Following that lunch in Manila, Halsey and MacArthur next

would meet at the formal surrender ceremony on 2 September in Tokyo Bay on

board the Missouri. But two weeks before that, after the Japanese

had announced they were quitting the fight and the announcement that MacArthur

was now Supreme Commander, the two men again would be closely allied. Under

Halsey, the 3rd Fleet would become MacArthur’s primary military resource in the

area surrounding Japan’s main islands. Under MacArthur’s orders, Halsey would

implement the first initial landings and occupation of U.S. military forces on

the Japanese main islands on 22 August.

Halsey tiptoed around what happened during that time in his

memoir. He deflected the fact that American soldiers arriving at Atsugi on 28

August were met with a sign reading: “Welcome to the U.S. Army from the 3rd

Fleet!” 20 Halsey cryptically attributed that to a renegade

fighter pilot from one of the carriers who landed without permission at the

Atsugi airfield and had the sign put up. We know now from his message of

21–2327 that the sign most likely had been put up by the landing force

installed there by Halsey himself on 22 August . The fact that Halsey dodged

the question is indicative to me that he—and others now reporting to the new

Supreme Commander—would defer to MacArthur for whatever he wanted the official

version of the times and dates of the occupation of Japan to be.

Later, on 29 August, Halsey would initiate the first

liberation of American prisoners of war in the Tokyo Bay area. This effort

started earlier than MacArthur had wanted, but as Halsey described it: “As with

the landings, circumstances forced us to jump the gun.”21 A

special Navy task force had been organized for this effort, and one of the

early evacuees was Major Greg “Pappy” Boyington, a highly decorated Marine

pilot who had been thought killed in an air battle over Rabaul. Halsey’s

Administrative Flag Secretary, Commander Harold Stassen, had accompanied the

Task Force when it liberated the Omori Prison Camp where Boyington was held

captive.

Halsey had indeed jumped the gun on the time schedule that

originally had been planned for liberating the POWs, but in this instance,

Nimitz gave his okay: “Go ahead,” he said to Halsey, “General MacArthur will

understand.”23 Until the end, Nimitz would retain control of the

liberation and evacuation of the Navy and Marine POWs from Japan.

Halsey had been a busy man from 15 August to 2 September. As

the media and the world became focused on the war’s end, MacArthur’s

appointment as Supreme Commander and his arrival in Japan to followed by the

formal surrender ceremony on board the Missouri—Admiral William S.

“Bull” Halsey had been “flying under the radar” of public attention,

successfully initiating the first landings of American troops, rescuing the

first POWs from defeated Japan, and organizing and leading the fleet as it

moved into Tokyo Bay. He would take General MacArthur’s order one more time from

the deck of the Missouri on 2 September—“Aye, aye, sir!” and

the planes would fly over the anchored ships. World War II was over.

Brigadier General William T. Clement, Fleet Admiral Chester

W. Nimitz, and Admiral William F. Halsey, USN go over plans at the Yokosuka

Naval Hospital, which had been taken over for treatment of released Allied

prisoners of war, 30 August 1945.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

A Personal Historical Perspective

One of these gifts was a white surrender flag made from

parachute cloth that had been hung on the propeller hub of a Japanese fighter

plane after its propeller had been removed. This was done by order of the

Japanese government at airfields across Japan as a signal to the Allied powers

that the planes would not be flown again in combat. Williams had taken one of

these from one of the planes at Kisarazu and had three Navy men sign it. The

first two signatures were readily identified—William F. Halsey and Harold

Stassen, who had been governor of Minnesota and then, in the Navy, had become

Halsey’s administrative chief of staff.

The third signature took some time and research to decipher

and then identify—T. S. Wilkinson. It was in Halsey’s autobiography that the

prominence of Wilkinson in Halsey’s life was revealed. He was one of those MacArthur

would have called “side-kicks from the shoestring SOPAC days.”24 He had

been one of the Navy men assigned to the command of General MacArthur in the

Southwest Pacific, and he reemerged at war’s end helping organize the

amphibious forces needed to begin the occupation of Japan. Wilkinson’s nickname

was “Ping,” and Halsey addressed him as a friend. Halsey mentions at one point

almost losing Wilkinson when the transport he was in, the USS McCawley (APA-4),

was sunk during the landings in New Georgia.25

The signatures appear to be in the same color ink and

grouped together as if they were all signed at the same time. Was there a time

when all three men—Halsey, Stassen, and Wilkinson—were together at Kisarazu

where Williams was stationed as part of the NATS base that had been established

there? Halsey said that he flew home through Guam, leaving Japan on 20

September 1945.26 Could Stassen and Wilkinson have accompanied Halsey on

that flight to Guam?

If so, one can visualize a young, inquisitive, junior

officer by the name of Haydn Williams walking up to this threesome who were in

good spirits, who had served together in a common enterprise in the far Pacific

throughout the war, celebrating their accomplishments and now anticipating

their immanent flight which would take them home. Halsey would have taken the

lead and probably said to Williams: “Hell yes, I’ll sign that flag!” and then

was followed by Stassen and Wilkinson doing the same.

The one thing we do know is that Haydn Williams could be determined

and dogged in his ways. We found that out during the site and design days of

building the World War II Memorial. At Kisarazu, he would have seen the flyover

spectacle on Tokyo Bay the day of the formal surrender. He knew that he was

seeing history made. Now, to have the chance of getting the signature of one of

the greatest U.S. Naval figures of all time—along with two of his close

friends—was an opportunity he could not forgo. I can see a young Haydn Williams

standing there on the tarmac as they boarded the big air transport plane that

would carry them home, clutching that piece of parachute cloth with three

signatures and knowing that he had been witness to a piece of American history

that would never be repeated.

--end--

1. Command

Summary of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (Gray Book), Vol. 8, message #19–0219, 3454.

2. Command

Summary of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, message #21–0517, 3464;

MacArthur and the allies were still learning the proper spelling of Japanese

cities and ports—Funakoshi is the place in reference, not “Fumakoshi.”

MacArthur also distinguishes between these “initial landings” being authorized

and later major landings which will be made on “H Hour,” and which will include

the airfield where the 11th Airborne will be landed. Those decisions must await

the success of the “initial landings” to be made by Halsey.

3. Command

Summary of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, message #21–2327, 3466,

3467.

4. Command

Summary of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, message #21–1431,

3357.

5. Command

Summary of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, message #21–2341, 3468.

6. Command

Summary of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, message # 21–0600, 3526.

7. Command

Summary of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, message #31–1745, 3482.

8. Reports of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of

MacArthur in the Pacific, vol. 1, 454.

9. Reports

of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific, vol.

1, 448.

10.

ADM William Frederick Halsey, USN, Admiral Halsey’s Story (Whittlesey

House, 1947), 126.

11.

Thomas Hughes, Admiral Bill Halsey: A Naval Life (Massachusetts:

Harvard University Press, 2016), Kindle location #109.

12.

William Frederick Halsey, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 152.

13.

Halsey, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 160.

14.

Halsey, 150.

15.

Halsey, 153.

16.

Thomas Hughes, Admiral Bill Halsey: A Naval Life (Massachusetts:

Harvard University Press, 2016), Kindle location #3662.

17.

Halsey, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 162.

18.

Halsey, 205–6.

19.

Halsey, 201.

20.

Halsey, 224.

21.

Halsey, 224.

22.

Halsey, 224.

`

24.

Halsey, 228.

25.

Halsey, 130.

26. Halsey, 235.